News 2007

Prevention

By Sharon Egiebor

In Denver, HIV/AIDS prevention workers inevitably get around to the conversation of highly-educated African American women and the rising rate of HIV infection among them. The chatter goes, if the women are so educated, why aren’t they smart enough to protect themselves from the HIV and other sexually-transmitted infections? Ru Johnson, program manager for Colorado AIDS Project, says people are confusing formal education with culturally relevant HIV prevention teaching. “People’s perception of their risk is slightly skewed,” said Johnson, who manages prevention programs for women and youth in communities of faith, with a specific concentration of communities of color. “Black women, are at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Denver and nationally because they lack HIV awareness and prevention education.” According to the U.S. Census, nearly 86.9 percent of Denver County residents have a high school diploma. An estimate 80 percent of African American women over 25 have a high school diploma or some college education, compared to 91 percent of white, non Hispanic women over 25 and 48.2 percent Hispanic women over 25. African Americans make up 11.5 percent of the Colorado population, but 17.6 percent of the new HIV infections in 2005. Colorado statistics mirror the nation, in that most of the new HIV infections are in men who have sexual contact with men (MSM), 64 percent. However, there are still a disproportionate number of African American women in Colorado who are newly infected with HIV, compared to the general population. “I’m not sure there is a connection between a highly-educated population and a high number of HIV infections,” Johnson said. “It is about the behavior, not the lifestyle. You can have a 35-year-old woman who is educated and she can be HIV positive.” Johnson said the woman may be unable to talk with her partner about safe sex or she may have become infected while in high school. “If you look at the age of those women when they were affected, 50 percent of all of those infected were considered youth, between the ages of 13-24 by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention standard, “ she said. “Formal education between 13 and 24 is not going to tell the story about their knowledge of HIV/AIDS. It will not tell whether they have been educated on prevention practices and STDs in general. Formal education between 13 and 24 is not where they’ve gotten the information.” Johnson, who joined the Denver-based AIDS service organization in November, said part of the problem is creating a sense of urgency with the prevention method. “We haven’t found a way to make people understand that it is an epidemic,” Johnson said. “There is still a disconnect in how we were teaching prevention back when HIV/AIDS was predominantly a white, male, gay disease and how we are teaching prevention now,” she said. “We as a prevention community in general have not figured out the strongest and most effective to reach these communities.” Johnson teaches at five-week HIV prevention program for African American women who are incarcerated in alternative jail facilities. Her agency targets women in jail settings because they know that African American women who are intravenous drug users between 20 and 40 years old are at high risk for acquiring HIV.

“When you are dealing with people of color, you have to understand which strategies are going to work and which are not. You have to understand the culture and the sociological foundation of why blacks are being impacted at such a disproportionate rate,” she said. “Regardless of what you see on television, black people do not have an inherited gene to acquire HIV. Blacks have a lack of trust in the medical system. A lot of folks don’t necessarily have access to information and may not know that they can get condoms for free at medical clinics.”

She is beginning an outreach to Denver’s faith community, specifically to the black churches. “This is going to be very tricky population to introduce to our prevention efforts as a whole. The church has traditionally been the foundation in the black community, understanding what those initial principles are and understanding what is going on today will be a fine line in how we blend together,” she said. “We are looking to find churches that are open to doing testing, or find churches that would be willing to provide prevention materials in a larger way by having prevention specialists come in and discuss HIV/AIDS or coming together to have a faith breakfast to discuss what are the barriers to getting this information to our community. A lot of times those barriers will include different avenues to presenting that information,” Johnson said. Johnson said the goal is to find a balance between the faith community beliefs and prevention guidelines. “We’ll discuss abstinence as an option to preventing a plethora of diseases and pregnancies, while still providing the most accurate, update strategy of those communities that are at risk.”

Profile

By Chris Bournea

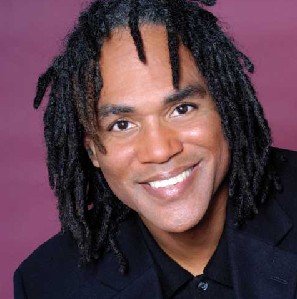

Actor Jimmy Jean-Louis is featured among the cast of the television phenomenon “Heroes,” about a group of ordinary people gifted with superpowers who are trying to save the world. In real life, Jean-Louis may not be taking on something ambitious as saving the world, but his mission of bringing awareness to HIV/AIDS is just as noble.

“It’s one disease that we can definitely stop if we try -- if you’re positive, don’t pass it on. If you’re not, try not to get it,” Jean-Louis said during a recent exclusive interview with Blackaids.org. “If we do this, within 15, 30 or 50 years, we can get rid of it.” The cause is one that literally hits home for Jean-Louis, a native of Haiti, which was widely believed to have incubated HIV when the virus first emerged in the early 1980s. Jean-Louis has not only worked to dispel that myth, he is using his high-profile status to bring much-needed awareness to HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention. “Back in the ‘80s when AIDS was discovered, they used to blame it on Haiti,” he said. “Therefore, all the Haitians from all over the world would be suspect for HIV or AIDS.” Being on an internationally popular television show such as “Heroes” has given Jean-Louis a platform on which to bring attention to HIV/AIDS and other important issues. “It shows the power of media, being on a hit show. As a person, I try to always bring some type of message that could help a lot of people that wouldn’t usually be serviced,” Jean-Louis said. “As a Haitian, first of all, I love that they call me ‘the Haitian’ on the show. Because Haiti has such a bad rap all over the world, and to have an actor on a successful show forces the world to know about Haiti, to have the name out there.” Born in Petion-Ville, Haiti, Jean-Louis left his native country in 1980 and moved to Paris, where he earned a business degree. His love of performing earned him a spot in Paris’ L'Academie Internationale de Danse. Although he grew up speaking French and Creole, Jean-Louis found that France did not always embrace citizens from its former colonies. “As a black person living in France, there are things that I wanted to get but I could never, never get,” he said. “Any hope of a high position in a job would be a huge challenge because we don’t have Black CEOs, we don’t have Black politicians [in France]. Those doors are closed to us over there. That’s why I started to move away from France, and from there I went to Spain, to try another country, to try my luck elsewhere. That’s where I started to work in musical theater.” Upon relocating to Barcelona in 1992, Jean-Louis spent two years performing in a musical production titled “La Belle Epoque.” He also lived in Italy and South Africa and he speaks five languages. Jean-Louis’ diverse international experience makes him an ideal ambassador to speak out on HIV/AIDS and other global issues. “As an actor, I try to take the important issues very seriously,” he said. “Millions of people might be listening. It’s a duty to try to send the positive message out there, whether it’s AIDS, what’s happening in Darfur, in South Africa, or even within the United States of America. It’s unbelievable to know that this is the No. 1 country in the world, but you still have poor people, you have people who cannot feed themselves.” Jean-Louis returns to Haiti several times a year and recently filmed a movie there about the HIV/AIDS epidemic called “The President Has AIDS.” The movie has been winning critical raves at the Pan-African Film Festival and other film festivals around the world.

“It was a way to spread the message, because the media’s not going to do it,” Jean-Louis said. “It can entertain, but at the same time there’s a message, there’s a lesson.”

Another recent film where Jean-Louis can be seen is opposite African-American comedienne Mo’Nique in the comedy “Phat Girlz.” In the movie, Jean-Louis plays an African doctor who falls for Mo’Nique and appreciates her curvaceous frame. “What I like about the movie is there’s interaction between the Africans and African Americans. There’s a clash there,” Jean-Louis said. “In general, I don’t think African Americans know a lot about Africa. It was one way to give them a little taste.” Jean-Louis can also be seen in the forthcoming film “Diary of a Tired Black Man,” which is scheduled for release in September. He has also begun filming the second season of “Heroes,” which debuts on NBC in the fall. Jean-Louis is concentrating on staying grounded, despite the phenomenal success of the show. “Ultimately, it’s just a job. I just go there and work like everybody else. The difference is as an actor, what you do is seen by millions,” he said. “When I start receiving e-mails from China, from India, from Germany or even Iceland, then I realize I’m part of something that’s really, really big.” The show’s global reach has made Jean-Louis all the more vigilant about raising his voice about HIV/AIDS and other causes. The devoted international following of “Heroes” has reinforced Jean-Louis’ belief that issues that impact one part of the world have ripple effects. “I always welcome people who come to me,” he said, “because ultimately we’re all the same.”

By the numbers

By Sharon Egiebor

Overall, abstinence and lessons on sexual responsibility appear to be clicking for non-Hispanic black youth, says Joyce Abma, Ph.d., a social scientist with the National Center for Health Statistics. The number of high school black youth who had sex for the first time in 2005 dropped from 82 percent to 68 percent. While that is higher than the 43 percent for white students and 51 percent for Hispanics students, another study indicates that black youth are using contraceptives, she said. Black youth reported in 2005 using condoms more frequently during their last sex act -- 69 percent compared to 63 percent for non-Hispanic whites and 58 percent for Hispanics. “In the case of non-Hispanic blacks, even though the sexual experience rate is higher, it is being offset by more consistent use of a condom and a greater uptake of the other contraceptive methods such as depo provero,” said Abma, who is based in Hyattsville, Md. “When we talk about these things generally, it seems a huge effort in programs, both community and private, to encourage teens to delay sexual intercourse and to approach it responsibly. The youth development programs emphasis over all positive development in all dimensions of life is probably important.” According to the National Survey of Family Growth, black youth are more willing to use some of the relatively new contraceptive methods, such as implants and injections of depo provera. In 2002, 27 percent of non-Hispanic black females reported using injectable hormone methods, 24 percent of Hispanic females and 18 percent of non-Hispanic white females. Abma says these statistics line up with data on teen pregnancy and live births. Among non-Hispanic black teens under 20 years old, the birthrate dropped 48 percent between 1991 and 2005, the largest drop among the three ethnic groups. In 2005, Hispanics had the highest birth rate at 82 per 1,000, followed by non-Hispanic blacks at 61 per 1,000 and non-Hispanic whites at 26 per 1,000. The number of students having sex with four or more partners is also dropping from 19 percent in 1991 to 14 percent in 2005. For non-Hispanic blacks, it was 28 percent, 16 percent for Hispanics and 11 percent for non-Hispanic whites. Most of the statistics were released recently by the Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, which pulled data from more than 20 government sources. The report also showed that: • In 2005, 47 percent of high school students reported ever having had sexual intercourse. This was statistically the same rate as in 2003. • The proportion of students who reported ever having had sexual intercourse declined significantly from 1991 (54 percent) to 2001 (46 percent) and has remained stable from 2001 to 2005. • The percentage of students who reported ever having had sexual intercourse differs by grade. In 2005, 34 percent of 9th-grade students reported having ever had sexual intercourse, compared with 63 percent of 12th-grade students.

Mobilization

By John Gordon

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- Brought together in one room, in an effort to end the silence and stigma of HIV/AIDS and the ravishing affect it is having on African Americans in the community, a very qualified panel, not only voiced their opinions, but offered valid and possible solutions for change. As African Americans only make up a small percentage of the population of the county, the most recent statistics released pertaining to the rate of HIV infection are staggering. It has been reported that as many as 40 percent of newly infected individuals are of African or Latino decent. "It is for this reason we must stop the silence, speak up, be heard, and get tested", says Manasseh Nwaigwe, a communicable disease specialist and A.D.A.M. project coordinator. The panel consisted of: Dr. Wilbert Jordan of Oasis Clinic, Dr. James Kyle II, Charles Drew School of Medicine, Min., Sam Casey of C.O.P.E., and Nosente A. Uhuti, coordinator of Ontrack (I.E.). Amongst the discussions of all panelists, Uhuti pleaded to the religious community, those present and not at the meeting, to be more accepting and loving toward individuals with HIV/AIDS and not to concentrate so much on how the disease was contracted by the individual. Pastor Julio Andujo of Amos Temple CME proceeded to counter Uhuti's statement by informing the participants that his church was different and is accepting of people in the community in need. In attendance at the meeting was an array of community leaders, individuals from other AIDS and health care organizations, as well as several other pastors. Additionally, several Riverside County employees participated in the discussion and shared some of their expertise on the subject matter. Families Living with AIDS Care Center, an organization founded by Curtis and Paulette Smith, a couple living with AIDS were also present, and they freely shared their experience of life with the devastating disease. The A.D.A.M. (African Descent AIDS Mobilization) project, which is coordinated by Mwaigwe, who is assisted by Azizi Ann Brown, has planned several more events to further discuss and develop solutions to fix the current way in which African Americans deal with HIV/AIDS and welcome the participation of any and all individuals who can assist in finding solutions to the problems faced in the community. The County of Riverside has set up several testing sites for the virus and welcomes anyone who feels they may be at risk to contact A.D.A.M. project toll free at: 1-877-NO DNIAL (663-6425)

Statement: Democratic Debate at Howard

By Phill Wilson

When the Democrats gathered on June 28 for the first of Tavis Smiley's All-American Presidential Forums, the conversation about AIDS was a far cry from the sorry spectacle of the 2004 vice presidential debate. In that 2004 debate, moderator Gwen Ifill asked both Vice President Dick Cheney and then-Democratic nominee John Edwards about confronting HIV among Black women. A befuddled Cheney replied that he was "not aware" of the problem; Edwards ignored the actual question and talked instead about AIDS in Russia and Africa. But what a difference three years, lots of activism and intrepid Black journalism makes. When NPR's Michel Martin asked about AIDS among Black teens in the June 28 debate at Howard University, the leading Democratic contenders took turns offering meaningful responses. “If HIV/AIDS were the leading cause of death of white women between the ages of 25 and 34, there would be an outraged outcry in this country,” declared Sen. Hillary Clinton, drawing rousing applause. “This is a multiple dimension problem,” Clinton concluded. “But if we don't begin to take it seriously and address it the way we did back in the 90s, when it was primarily a gay men's disease, we will never get the services and the public education that we need.” Barack Obama urged African Americans to challenge stigma surrounding the virus, and notably cited homophobia as a roadblock. “We don’t talk about it in the schools. Sometimes we don’t talk about it in the churches,” said Obama, who talked about AIDS in white evangelist Rick Warren’s church. “It has been an aspect of ….homophobia that we don’t address this issue as clearly as it needs to [be].” Obama added that AIDS is but one more symptom of the larger, “interconnected” problems we face. “The African American community is weakened,” he declared. “It has a disease to its immune system.” Joe Biden urged African Americans to get tested and to discard unhealthy notions of Black masculinity that discourage both condom use and sexual communication. John Edwards outlined three clear policy priorities for stopping AIDS, which included boosting spending to find a cure, guaranteeing universal treatment for people living with AIDS, and expanding Medicaid to cover HIV – a crucial initiative that advocates have tried and failed to get on Washington’s agenda for a decade, and which Clinton highlights on her campaign Web site. Black America has finally convinced presidential candidates that if they want to get our support, they have to meaningfully discuss AIDS – at least when they are talking to us. Now we’ve got to make them put their platforms where their mouths are. Show us the plan, Mr. and Mrs. Candidate. Show us the plan. The AIDS story is primarily one of failed leadership, and it's time for our leaders – and our wannabe leaders – to actually lead. No candidate in either party has put forward a plan for dealing with AIDS in the United States, let alone a plan to end the epidemic in Black America. And no candidate should receive a dime from us, let alone our votes, without one. This demand is a crucial one. An Open Society Institute report highlighted in May that America today has no overarching plan guiding our national response to an epidemic that has killed more than half a million people and left as many as 1.3 million living with HIV/AIDS today. There are no listed goals. No benchmarks for success. No delineation of the resources needed. As my grandmother used to say, “If you fail to plan, you plan to fail.” Black America suffers most from this lack of focus. We account for half of all people living with HIV/AIDS and half of all new infections each year. As Martin noted in her question to the candidates, our children make up 69 percent of new cases among teens. Black women represent two-thirds of female cases. Forty-six percent of Black gay men may already be positive.

So any candidate credibly asking for African American votes must show how he or she plans to end the epidemic in Black America. We must not accept vague promises alone, but must insist that candidates lay out detailed proposals.

The candidates don't have to start from scratch in this process. Last summer, Black community leaders stepped into the void and began plotting a national mobilization to end AIDS in Black America. Twenty-five national Black institutions have since signed on to the effort, which boasts signatories that range from the NAACP to Snoop Dog, Ludacris, Don Cheadle and Beyonce. Every presidential candidate should sign on to this historic mobilization as well. The time for haphazard, reactionary policymaking in confronting AIDS is gone. The emergency of the epidemic's early years has long since morphed into a lasting, increasingly complex problem that demands a solution born from proactive planning. Black Americans cannot afford to accept anything less. So here is what we need to do. Anytime we communicate with a presidential candidate-by mail, email, telephone or in person-ask this question: What is your plan to end AIDS in the Black community?