In This Issue

Last week, I went participated in a CDC consultation on HIV in the South.

The purpose of the consultation was to get feedback from activists, ASO's, health departments and researchers on how to develop and/or implement High Impact Prevention strategies that address the HIV-related disparities between the South—Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Arkansas, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Florida—and other regions of the country.

During the one-day meeting, we looked at barriers and challenges, and current and best practices. Finally, we made recommendations to CDC, HRSA, NIH, NIAID, and OMH to create a better response. The meeting concluded with a robust Q&A session with CDC leadership.

One of the first things acknowledged was that disparities exist based on race, sexual orientation, poverty and geography. Health and HIV disparities based on race and health and health and HIV disparities based on living in the South happen both together and separately. Some disparities—think: stigma, attitudes about sexual orientation, and whether or not a state expanded Medicaid—impact people living in the South, regardless of their race. But because a high percentage of Black Americans live in the South and a high percentage of people living with HIV in the South are Black, you can't address Southern health and HIV disparities without addressing Black disparities.

One of the major contributors to HIV-related health disparities are systems that are either ineffective or create barriers, in and of themselves. For example, funding streams that come from federal agencies in silos can make it difficult to provide comprehensive services across funding streams and agencies.

These are among the most important takeaways from the consultation:

1) The messenger matters. Building infrastructure among communities most at risk is critically important.

2) Acknowledging that structural and social determinants of health have to be addressed if we're going to have success in high impact prevention. Right now, we focus on the number HIV tests, the number of positives found, the number linked to care, the number retained in care. That's based on the assumption that HIV is at the top of someone's priority list. We're finding that HIV is not necessarily at the top of every individual's priority list. Housing stability, food stability, un- or underemployment, intimate-partner violence, poverty in general —these are the things often at the top of many individuals' agenda. If these things are not being addressed, the person doesn't have the bandwidth or capacity to care enough about HIV/AIDS issues. That means organizations that are attempting to respond to HIV/AIDS episodes in these communities, especially in Black communities and among gay and bisexual men, need to spend time paying attention to social determinants of health—connecting people with essential services, for example. But the funding doesn't prioritize linking people to essential services. The funding needs to include linking people to essential services as a legitimate HIV-prevention tactic.

3) The current level of expectation is not always based on the reality of the client served or region of country where they receive services. For example, take a single, middle-class White gay man living in San Francisco, without children, who is gainfully employed and finds out he has HIV. It might not be that difficult for HIV to be a major priority in his life, so he can spend all his time worrying about his ARVs. But for a single Black woman in Macon, Ga., who has two children, the things that the agency that provides service has to do for her before she has the bandwidth to think about HIV may be significant. Yet the expectations are that you can respond to the needs of the Black woman in Macon with no additional resources than the single White gay man in San Francisco—and that you're going to have the same impact as quickly. Our expectations need to reflect the people we serve and the environment in which we serve them.

Maya Angelou one said, "When we know better, we do better." We actually know a lot about the challenges and barriers to ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the South and the rest of the country. The question is do we have the will, political and otherwise, to do better.

In this issue, we report on the Institute's recent Brown Bag Lunch Webinar "HIV Myths and Facts," since challenging the inaccurate urban legends about HIV and AIDS that circulate in many communities literally can mean the difference between life or death. We also run a piece about new research identifying a possible relationship between having hepatitis and the likelihood of developing Parkinson's disease.

One of the unexpected outcomes of the Republicans' attempt to "repeal and replace" the Affordable Care Act (also known as Obamacare) is that some states that declined the Medicaid expansion are now revisiting that option. Our friends at Kaiser Health News report on that story as well as the next steps the GOP is taking to gut Obamacare. From shorter enrollment windows, to tighter vetting of people who sign up outside of those open periods, to efforts to require some consumers to show proof of prior insurance coverage, the Trump administration's proposed rule changes will make it harder for people who purchase their health insurance in the health insurance marketplace to obtain coverage.

Finally, our friends at ProPublica report on one Trump administration official that the LGBT community might want to keep close eyes on, given his history of attempting to purge gay employees during the Bush years.

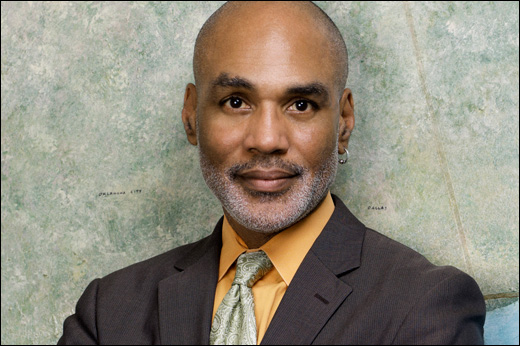

Yours in the struggle,

Phill