How Obamacare Went South In Mississippi, Part 7: 'A State-of-the-Art I.C.U.' Shuttered

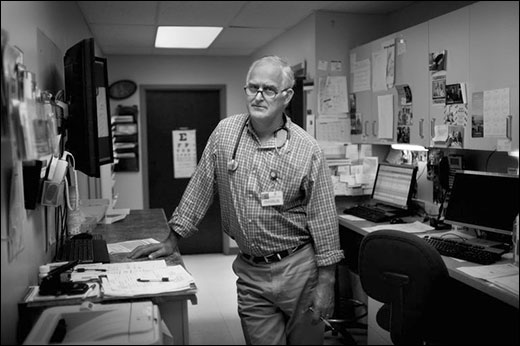

Dr. Tim Alford in his clinic in the central Mississippi town of Kosciusko. The hospital across the street has had to lay off staff and shutter its I.C.U.

Jimmie Lewis, 44, greets a friend in the neighborhood. Lewis pays about $33 per month for his ACA insurance.

In the country's unhealthiest state, the failure of Obamacare is a group effort. Go here to read Part 6.

Poor people often flocked to the emergency room at Montfort Jones Memorial Hospital in Kosciusko. The central Mississippi town is best known as Oprah Winfrey's birthplace, but the distinction has done little to change the town's fate. Unemployment in Attala County is far higher than the state average; nearly one in 10 adults is out of work, and Montfort Jones has added to those numbers of late.

Earlier this spring, the hospital shuttered its intensive care unit and laid off 38 employees. Next, the psychiatric unit for seniors closed. One in five people who come to the emergency room can't pay their medical bills, and the hospital relied on supplemental Medicaid payments to defray the costs. But under the health law, federal aid for uncompensated care trails off on the assumption that hospitals should be able replace much of the lost income with newly insured Medicaid patients. Without them, and with no softening in the demand for uncompensated care, Montfort Jones has been losing $2 million to $3 million a year, and couldn't meet payroll.

Tim Alford is a country physician who likes to say rural doctors in Mississippi practice "real medicine." At Montfort's emergency room, across the street from his family medicine practice in Kosciusko, he attends to stroke patients, heart attack victims and, the week I met him in June, an energetic 3-year-old boy who had somehow managed to bite a hole through his tongue. Montfort was one of the original hospitals built under the Hill-Burton Act, a post-World War II, government-financed hospital construction program that brought economic life to many of Mississippi's rural byways. The hospital, along with its intensive care unit, was rebuilt just a few years ago into a modern, rural gem.

Alford led me down a darkened hallway and pushed open the doors to the ICU. It looked as if the nurses, doctors and janitors, after tidying up and making the beds with fresh linens, had just gotten up and left. Scanning the bay of ghostly patient rooms, Alford said mordantly, "This is a state-of-the-art ICU." Now, patients with pneumonia, blood clots or infections that need monitoring are sent 70 miles away to Jackson. Nationally, two of the five hospital systems with the largest financial margin declines are located in Mississippi, and there has been a spate of closures and layoffs at rural hospitals in Mississippi in the last year alone.

During state budget negotiations in the fall of 2013, Gov. Bryant proposed giving the state's struggling hospitals $4.4 million to offset their losses. The Mississippi Hospital Association's new chief executive officer, Tim Moore, responded politely to the gesture, saying, "We appreciate the governor's acknowledgment that hospitals are in need of financial help to recover from severe cuts to reimbursement on both federal and state levels," Moore told the Associated Press last December. "Any restoration in funding to our state's hospitals is truly appreciated."

Democrats viewed the earmark as hush money. "I've asked the [hospital association] a number of times what they got in exchange for their deciding to become mute on this issue," state Sen. Hob Bryan, the Democratic vice chairman of the health committee, told me. "They said they got a seat at the table. I said, 'So, in other words, you sold your birthright. You didn't even get a bowl of porridge. You just get to sit at the table and watch other people eat porridge?'"

The proposal left many economists and hospital experts scratching their heads: With its modest coffers, Mississippi couldn't come close to making hospitals whole. They were facing eviscerating cuts in federal subsidies of $8.7 million in 2015 and 2016; $26 million in 2017; $72.3 million in 2018; $81 million in 2019, and $57.8 million in 2020, according to the Center for Mississippi Health Policy. Over breakfast one morning in Jackson, Ronnie Musgrove, a Democratic former governor told me, "It just defies logic."

The indignity cut much deeper for Dr. Alford. Governor Bryant's insistence that Mississippians in need of health care could head to an emergency room was, to Alford, an insult to rural doctors desperate to improve the health of their community, not serve as medics on a battlefield. It guaranteed the state would be locked in a failed system. "The emergency room is the wrong place, exactly the opposite place, that a lot of these people should be going," Alford told me at his clinic across the street from the hospital in Kosciusko. "That is a shallow, irresponsible answer to the problem." All those diabetes-related amputations, heart attacks and breast cancer deaths could be warded off or controlled with good primary care.

Now that he is sending most patients in need of intensive care all the way to Jackson, Alford said, "The silence from the state capitol is deafening." Alford said. Obamacare wasn't perfect, he acknowledged, but the law's instinct to divert patients from high-cost settings to primary care was Mississippi's best shot at moving out of last place. "If that's where we're content to leave it," Alford said, "if this is the best we can do, then we're in a peck of trouble."

A Personal Triumph

The afternoon heat was closing in like quicksand in Jackson one day in June during my visit, and soon every molecule inside every living thing would become stuck to the next one. The only answer, of course, was to jump in a pool or eat a New Orleans-style snowball.

For 18 years, Jimmie Lewis, has been towing his cherry red snowball trailer behind his truck to the city's public pools. He does a brisk business selling syrup-flavored shaved ice— sour apple, rainbow, strawberry daiquiri—as the summer temperatures soar. After the state hospital where he worked closed and he lost his job, Lewis attended an entrepreneurship class at Jackson State University. He used a student loan to buy his first trailer and then added two more. His eldest son and his cousin usually helped him out, but neither could work this summer. Jimmie, 44, advertises his business as "Christian Owned and Operated," and spends six to seven days a week driving his food truck during warm months. "It's like farming," he told me. "You gotta get it when you can."

Despite the success of his business, Lewis could never afford health insurance and had gone without it since 1995. His body held up okay, though he went through a divorce and battled depression. What worried him most at the time was getting in an accident and not being able to provide for his three kids.

But earlier this year, Lewis saw a television news story about an Obamacare sign-up center and went down to enroll. The plan he picked came with dental insurance (that had been his true motivation—he needed a tooth pulled), and the whole package cost him about $33 per month.

It was a practical and financial fix, to be sure. "Before, man, you don't have any choice," Lewis told me. "You get sick and go the emergency room. Then you owin' everyone around town if you couldn't pay the bill." But more than that, it was a personal triumph. When Lewis' insurance card arrived in the mail, he felt like he had finally made it. "Oh, man, I could poke my chest out. I'm self-employed and insured. That's something I hadn't had, so I was really proud of it. I'm still proud of it."

On the day I met him, Lewis pulled into the parking lot at a busy public pool in Jackson's North End, an African-American neighborhood, and with the heat index at 100 degrees, a line quickly formed in front of his concession window. Khadijah Garrett, 20, and her friend Victoria Hughes, 20, ordered lemonade and strawberry snowballs. Neither had health insurance—Hughes had missed the deadline to sign up, and Garrett had just been too busy. "I'm working two jobs," Garrett told me, her lemonade-flavored ice melting quickly. Monday through Friday, she was a janitor working for a cleaning service, and at night she waitressed at a barbecue restaurant. Her mother had signed up for Humana insurance through Obamacare. "She said it's good. They'll cover half of a $2,000 bill, and my neighbor, he pay 24 cents for Humana," Garrett said. Why hadn't she signed up then? "I was too busy. I don't got the Internet around me." Others here at the pool told me similar stories: Too busy working too many jobs to find the time.

I asked Garrett what she made of her governor's plan to create jobs with health benefits that uninsured workers like her could move into. "No offense," said, Garrett, who is black, "but we got a little racial issue here in Mississippi." As if that explained everything to me, the pool's only white visitor.

Many of Lewis' friends and customers didn't earn enough to buy insurance on the federal exchange as he did – they fell into the Medicaid gap. "I know guys who wash cars every day, and it's hot," he explained. "They fall down and have a stroke or somethin', they don't have any health insurance. And where's the money gonna come from? His family is depending on him."

Lewis had followed the news about Bryant's opposition to the Medicaid expansion. To him, it made sense that white conservatives wouldn't want people like him—blacks—to have Medicaid; people in Mississippi have learned to deal with bigotry. But it surprised him that Republicans in the state were leaving white people in the Medicaid gap, too. "As long as you don't step on my shoes, and I don't step on yours, man, we can live and coincide," he said. "But when you're white and do that to other white people? Man, that's mean-spirited."

By Sarah Varney

Jeffrey Hess of Mississippi Public Broadcasting contributed to this story.

This article was reprinted from Kaiser Health News with permission from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent news service, is a program of the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonpartisan health care policy research organization unaffiliated with Kaiser Permanente.