Why an Educated, Informed HIV/AIDS Workforce Is Essential for Ending The AIDS Epidemic

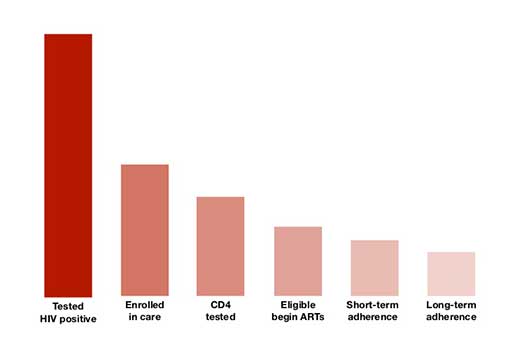

Treatment cascade

While the paradigm shift from behavioral to biomedical prevention might seem at first to diminish the role of community-based HIV/AIDS workers, "The HIV workforce is as important as ever," says Danielle Houston, senior program advisor of the National Minority AIDS Council's Treatment Education, Adherence and Mobilization Team.

Indeed, as the nation implements the Affordable Care Act (ACA), including expanding Medicaid, the non-medical HIV workforce—providers of HIV/AIDS health care services, such as case managers, public health workers and advocates, policy makers, contractors, volunteers, and people living with HIV—continues to play a vital role in the effort to drive PLWHA's viral loads to undetectable levels and end the epidemic.

The Biomedical-Behavioral Connection

Every biomedical intervention depends on the behavior of the person who must carry it out.

"I've been living with HIV for thirty five years now," says Phill Wilson, President and CEO of the Black AIDS Institute. "Every night when I look at the meds that I'm about to take, I'm face to face with the reality that I have an essential role to play in my own health. The meds can remain in their bottle, or I can take them. What the pills do is biomedical. What I do is behavioral."

Although the tools in the nation's biomedical toolkit are largely prescribed in clinical settings, clinicians are not behavioral experts.

By contrast, the HIV/AIDS workforce has almost 35 years of expertise in understanding and addressing the needs as well as influencing the behavior of PLWHA.

"Suggesting that primary HIV prevention is exclusively or even primarily clinical misses the point," says Wilson. "Our goal should be to integrate the biomedical with the behavioral, as neither one is sufficient without the other."

Becoming Fully Informed and Actively Engaged

As the ACA expands the universe of health care providers who work with PLWHA, HIV workers can help ensure that people who newly enter the system actually obtain the health care they need.

"Increasingly, people living with HIV will be receiving their care not from a Ryan White clinic or a community-based AIDS organization but from community health centers and other less specialized providers," says Moises Agosto, director of the National Minority AIDS Council's Treatment Education, Adherence and Mobilization Team.

New access points and novice HIV/AIDS care providers can inadvertently create ways for people to fall out of the healthcare system, including as it relates to preventing HIV, getting people tested and linking them to care and treatment.

"We need to rapidly increase testing of at-risk populations and get those people into care," says Mark Harrington, executive director, of the Treatment Action Group. "All those things can't be done in the medical setting. The doctor simply doesn't have enough time to explain everything an individual needs to know." Facts like why they should get tested, why adherence is so important, how to interpret their lab results and how to develop a strong, open relationship with their health care providers are vital to the wellbeing of PLWHA.

The HIV/AIDS workforce knows how to deliver treatment education in a language that patients can understand. As trusted members of their communities, they can help dispel myths about HIV testing and treatment.

Supporting High Level Care

While clinical sites can employ automatic call-backs before appointments and other practices to promote retention in care, most lack the capacity or expertise to help patients remain engaged.

"As people increasingly get their care from providers who have less experience in treating patients with HIV, ensuring that consumers are fully informed and actively engaged in their own care will be more important than ever," says Agosto.

HIV workers are typically better suited to recognize and address housing instability, substance use issues, poverty, depression and other non-medical challenges. They are also experienced in supporting the high level of self care strongly linked to good health outcomes among PLWHA.

"HIV is now a bit like diabetes," Harrington notes. "Effectively managing HIV infection requires a lifelong commitment to behavior change and health promotion."

While research shows that brief educational interventions during the delivery of clinical care can improve treatment adherence for a number of health conditions, strong community-based programs can offer more intensive peer-based education and support. For example, PLWHA can learn from each other over time, in the process building and reinforcing knowledge about HIV-related self-care through collaborative learning models.

Peer-based patient navigators can help patients overcome challenges associated with complex health care financing and delivery systems.

"There is a huge role for community health workers and peer health navigators," Harrington says. "We know from drug addiction treatment and programs for the homeless that peer groups and peer navigators can really help people stay in care."

Promoting Care among the HIV Negative

HIV/AIDS workers can promote health care access among people who are HIV negative, also. Those who are well, especially younger people, often perceive little reason to access health care services regularly.

New York State's plan to end the epidemic—a plan jointly developed by community advocates and political leaders—aims to use Medicaid expansion to link high-risk HIV-negative people to regular health care. In turn, that care can become a platform for delivering a combination of prevention approaches.

For this vision to become a reality, though, HIV workers must play a central role in educating community members, motivating them to access care and assisting them in navigating the rapidly evolving health care landscape.

"The solution is to link community-based organizations to provider networks," says Harrington. Indeed, innovative partnerships between clinics and community-based organizations offer an unusually effective model to help patients maintain their HIV care.

Strong HIV science knowledge is likely to play a critical role in uptake of PrEP and other biomedical prevention tools. Indeed, high knowledge levels are closely linked with HIV workers' willingness to promote these interventions, the findings from the "U.S. HIV

Workforce Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Survey," the largest survey ever conducted of non-medical personnel working in HIV/AIDS in the United States, showed.

The study, conducted by the Black AIDS Institute in partnership with the CDC, the Latino Commission on AIDS, the National Association of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD), Johns Hopkins University and Janssen Therapeutics, surveyed more than 3600 participants from 48 states, Washington, D.C., and the U.S. Territories.

More Than a One-Hour Training

Shockingly, despite their many years of experience, non-medical personnel working in the HIV/AIDS field demonstrated inadequate knowledge of biomedical interventions.

HIV workers scored a 46, or an F, on questions about biomedical interventions and a 56 (also an F) on questions related to treatment. The results also showed that many HIV/AIDS workers don't believe the scientific evidence that shows that these biomedical technologies are effective.

The workforce scored the highest—a 76, or a C—on basic knowledge and terminology questions.

"We need to figure out how to restructure the HIV workforce so it can function in this new framework," says Harrington. "It is clear that the HIV workforce has decades of useful experience, but now we need to ensure that medical training is part of their skill set."

"It would be a shame to have these tools that we've developed through research not be used because we've not invested in the training needed to get us to zero," says Leisha McKinley-Beach, HIV program administrator for the Fulton County Department of Health and Wellness in Atlanta.

But building the HIV science and treatment capacity of the HIV/AIDS workforce can't be achieved on the fly.

"We need a long-term educational and professional development plan," McKinley-Beach says. "If you just take PrEP as an example, the HIV workforce not only needs to know basic information about PrEP but also about how to integrate the intervention in HIV counseling and testing and in other components of the prevention continuum. This is not something that can happen in a one-hour training."

Adapted from the Black AIDS Institute Report, "When We Know Better, We Do Better: The State of HIV/AIDS Science and Treatment Literacy in the HIV Workforce," published on February 5, 2015.