Sex, Lies and HIV: When What You Don't Tell Your Partner Is a Crime, Part 6

The sixth in a series of stories on HIV stigma and criminalization.

One consequence of the viral exposure legislation is that public health activities and law enforcement, which have traditionally been kept separate, can now overlap. In some states, such as Mississippi, people who test HIV-positive are routinely asked to sign a document called a "Form 917." By signing it, patients acknowledge they have been counseled about the basics of living with HIV, including the legal consequences of not telling partners they have the virus. Similar forms have also been used in Arkansas, Michigan and North Dakota.

In several states, including Idaho, Missouri, Indiana, Michigan and Iowa, ProPublica found, prosecutors and judges have used subpoenas and warrants to force health officials to hand over these forms along with other medical records, such as test results, as evidence against patients charged with violating viral exposure laws. County prosecutors in Indiana, for example, have served at least 20 such subpoenas to the state health department since 2010.

Sometimes, health officials have initiated criminal proceedings. In Grand Traverse County, Mich., former county health officer Fred Keeslar sent a memo to the local prosecutor headlined "Recalcitrant Behavior," suggesting that police set up a sting operation to arrest and prosecute an HIV-positive man suspected of cruising for sex in public bathrooms without disclosing his status. Keeslar did not respond to requests for comment.

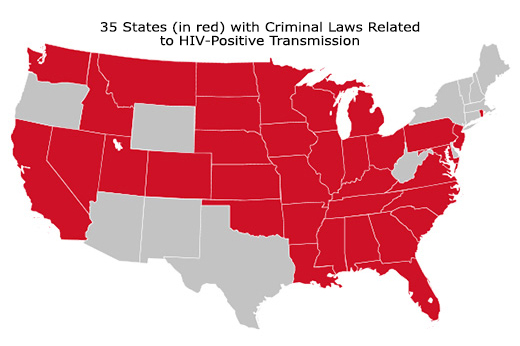

On the federal level, Obama administration officials have come out against HIV-specific criminal laws. In 2010, the White House's Office of National AIDS Policy issued a white paper saying that the "continued existence and enforcement of these types of laws run counter to scientific evidence about routes of HIV transmission and may undermine the public health goals of promoting HIV screening and treatment." The Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS has also condemned these laws.

In 2011, the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors, or NASTAD, also endorsed the repeal of laws that criminalize HIV exposure or nondisclosure. (Last June, NASTAD also filed a friend-of-the-court brief in the Rhoades case.)

But across the states, health officials have varying opinions. "The existence of the statutes does not affect our prevention, diagnosis and treatment efforts," a spokesman for the Virginia state health department said.

But Jill Midkiff, a spokeswoman for Kentucky's Cabinet for Health and Family Services, said that "imposing harsher sentences on individuals with HIV or treating HIV-positive patients differently in the eyes of the law may impact the effectiveness of the Department of Public Health's HIV prevention efforts."

And Donn Moyer, a spokesman for the Washington State Department of Health, said, "we believe it's time to look at the effectiveness of such laws, given current knowledge and understanding of HIV transmission and treatment, which have advanced a lot since most of those HIV laws were written."

Officials in Louisiana did not comment on specific criticisms of its law, but internal emails discussing ProPublica's questions show how sensitive the topic can be. One former health department spokeswoman told a colleague it is "a touchy topic that will require governor's office involvement."

In Tennessee, ProPublica's questions were sent to the state epidemiologist, who told a spokesman: "Ain't touching it with a 10 foot pole."

In Iowa, the Rhoades case helped spur a bill that would lower the penalties for HIV exposure, but it failed to pass. Its lead sponsor said he plans to reintroduce it. For anyone who intentionally tried to infect someone, the punishment would remain harsh: 10 years if infection occurred, and five years if it didn't. In cases where someone didn't intend to infect his partner but still did so after failing to take "practical means to prevent" transmission, the penalty would be two years. If there was no intention to infect and no one was infected, there would be no penalty. Local AIDS activists and the state health department support the bill, but some prosecutors still oppose it.

By Sergio Hernandez, Special to ProPublica

This story was co-published with BuzzFeed.