In This Issue

On May 25th HBO aired the film adaptation of Larry Kramer's 1985 play The Normal Heart. HBO and Ryan Murphy should be congratulated for bringing Larry's experience of the beginning of the AIDS epidemic back to life in such a vivid and emotionally authentic way and for initiating a new discussion about the AIDS epidemic. This film is definitely a must see.

It was an extremely painful and difficult film for me to watch. I started crying five minutes in and didn't stop until long after the final credits ended. It was difficult because I remember those days vividly. I remember the fear and the panic. I remember my friends dying painful and horrific deaths. It was difficult to watch because, as powerful a story as The Normal Heart is, the film is also a painful reminder of how invisible Black people dying from AIDS were then and how that invisibility continues to plague efforts to fight the epidemic today. It was difficult to watch because while the film is generating a new conversation about HIV/AIDS, much of that conversation is about "how it was"; not enough of the conversation is about "how it is". The HIV/AIDS epidemic is not over!

I actually saw the film at a premiere in West Los Angeles with the director Ryan Murphy and one of the stars, Matt Bomer. I left the theater wondering whether the stories of Black people who died from AIDS and those who fought the epidemic in the beginning will ever be told?

The Normal Heart is one of a number of recent films about the early days of the AIDS epidemic—The Dallas Buyer's Club, We Were Here and How to Survive a Plague, among them. Watching these films—each one, extremely powerful—one would be led to believe that there were very few if any Black people or people of color involved in fighting the AIDS epidemic during the early days, that the only people dying from AIDS were White gay men, or that the only reason our society ignored the disease was because of homophobia.

Today, these omissions are particularly tragic. These misperceptions delayed a Black response and left Black people, including Black gay men, with a false sense of security or protection. The AIDS epidemic has always disproportionately impacted Black people. AIDS is and always has been the manifestation of the whole cloth of oppression and marginalization: homophobia, sexism, poverty, racism and so on.

One reason why the AIDS films being made today about the early days of the epidemic are primarily about White gay men is that some people who have the power to green light projects want the world to know what the epidemic was like for them. I'm not mad at Ryan Murphy, Larry Kramer or anyone else for telling their story. Indeed, I desperately want people, especially Black people to see The Normal Heart. But I want Black people to learn from the film that we have to care about ourselves. We can't wait for someone else to fight the disease for us. We can't wait for someone else to tell our story. We need to do it ourselves.

Most importantly, however, I'm concerned about what that story is. For instance, is it a story about a people who are distracted by fear and stigma or is it a story about the power that comes from a people committed to saving ourselves? The entire Black experience in America is one of perseverance and overcoming obstacles. It's heartbreaking when we lose sight of that. Our HIV story should be one of a people making heroic sacrifices to save ourselves and our loved ones. We need to tell that story. We need to make sure that our loved ones lost in this war are not forgotten. We need to tell the whole story from the beginning with a commitment to fighting to the end. It will talk all of us to make the history and it will take many of us to tell the story. That's the movie I want to see.

In this issue we learn about Marcus McPherson, a Mississippi resident once served by the Black Treatment Advocates Network (BTAN) who has now become a BTAN activist. We also report on the second annual Saving Ourselves Symposium for Black MSM, which begins this Thursday in Memphis. We run a story from our friends at Kaiser Health News about the public debate surrounding two new, but very expensive, drugs to treat hepatitis C. A reader asks whether insurers must cover the cost of PrEP now that the CDC recommends it. Finally NASTAD data show that ADAP continues to play a vital role in the lives of PLWHA who have health insurance and those who don't.

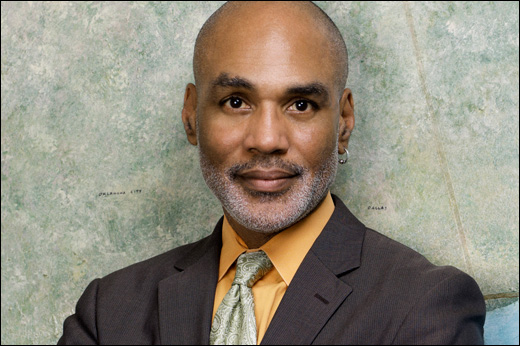

Yours in the struggle,

Phill