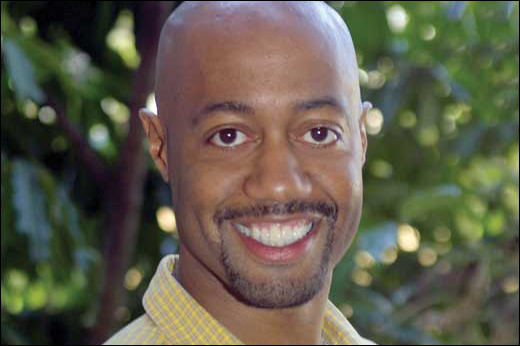

Coming Out: Craig Washington

One in a series exploring the lives of people who have chosen to be out about their positive HIV status.

I aggressively hid my infection in the summer of 1985 when the lymph node below my left ear swelled first to the size of a raisin, then a walnut. I can clearly recall one moment two or three years later, standing at a corner in New York City's Greenwich Village, explaining to activists Colin Robinson and now-deceased Craig G. Harris that my lymph nodes were swollen because of sarcoidosis. They knew that I was lying, and I found their pity embarrassing.

It was not until I arrived in Atlanta in 1992 and heard Debbie Thomas-Bryan -- also now deceased -- speak at the "All Walks of Life" AIDS Walk that I considered publicly disclosing my status. Her testimony seemed to flow from someplace ancient and unshaken within her that sought neither approval nor acceptance. I wanted to find that core inside myself and live up to the standards of integrity that brave Black men like Colin, Craig and others set.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic that we once called a holocaust looks much different today. Yet Black men are still being pummeled by the assaults of poverty, racism and racial disparities in the rates of HIV infection, prevalence and viral-load suppression. Stigma oppresses us as well, not only by causing our families to reject us and causing us to avoid seeking health services, but also by poisoning our perceptions about ourselves and our brothers, in the process cutting off the love only we can offer one another. Black gay men regarded as femme, fat, soft-bodied, old or sick (HIV positive) need not venture outside our own landscape of social media and HIV-prevention palm cards to encounter blistering "shade."

Today Black gay male activists speak at Black gay-pride events, where we communicate messages like "There is no shame in being HIV positive" and "We Are > AIDS." We facilitate 3MV sessions and support young people in our lives. We demonstrate leadership both within and outside the AIDS workforce and model affirming expressions of Black gay personhood. Yet when it comes to our positive HIV serostatus, many of us who carry a neon sign about our sexual orientation remain conspicuously discreet.

How do we reconcile the explicit messages that we communicate to our brothers and sisters to counter their fear of coming out about their sexual orientation with implicit messages when we stay in our closets about our own HIV-positive status?

It's important that we acknowledge factors that we already know impede poz leaders from coming out and recognize those we have not yet considered. Those of us who work for AIDS organizations or other relatively progressive employers may face lower risks of losing our jobs, insurance coverage or workplace status than others do. However, our role as advocates doesn't always protect us from others' scorn and isolation. And many Black HIV-positive gay men live and work in environments that are unprotected from discrimination or in "right to work" states, where they can be fired without cause.

Leadership has its hidden costs, too. For example, what happens if someone who urges condom use turns up HIV positive himself? How will others think of him, especially if his diagnosis was recent? Will those of us who are HIV positive be cast as fakers or failures when we warn the HIV-negative about the enduring perils of becoming infected and reassure the HIV-positive that their infection is manageable?

I came out in order to be free, but this freedom carries a toll. When my Jackd alert read, "You Have a New Message," I was not prepared for it to read, "OLD AIDS INFECTED FAGGOT." I did not recognize the round brown face alongside the four words written to sum me up. When I responded, "Yes I am. What does that mean for you?" my assailant, "Jay," shot back, "Use a rubber, blood tainted punk."

HIV-positive Black gay leaders must assess the threats that disclosure presents to us and summon the courage that the work demands. This requires not only engaging in the personal work of assessing our individual risk and readiness but also continuing the collective work of dislodging stigma as well as legal and social discrimination (including HIV criminalization), enhancing and widening our leadership base and achieving the justice we deserve.

We are many men with many voices that must be raised higher than ever before.

Craig Washington is a prevention programs manager for AID Atlanta, Inc.