News 2005-Older

From ColorLines magazine

By Kai Wright

Garry Wayne Carriker had a pretty promising life ahead of him. He'd graduated from the Air Force Academy back in 2001 and at age 26 was prepared to graduate from Emory University's prestigious medical school this past spring. He probably never dreamed he'd instead spend most of the year sitting in an Atlanta jail. But at summer's end, that's just where he was, awaiting trial on three counts of a sex-crime that could get him 30 years behind bars. Carriker's not a rapist or a child molester, but many consider his alleged crime equally horrific. The Atlanta attorney who is representing one of Carriker's seeming victims in a civil suit compared his actions to "shooting bullets into the crowd." Carriker is charged with having consensual sex with a guy he was casually dating without telling the man he is HIV positive. He was arrested and released on bond, but then two additional men came forward with similar charges. So a judge locked him back up, where he remained at this article's writing. Publicly, it's still unclear when or how Carriker found out he was positive. It's also unclear exactly what sex acts he and his boyfriend, John Withrow, engaged in together, or if they used protection when doing anything in which HIV could have been transmitted. Not that any of those details matter much to the law. Nor does it matter that Withrow never actually contracted HIV. All that matters is that Carriker had sex without telling. In Georgia, as well as in dozens of other states, that's a prosecutable offense. Carriker, who is white, is the latest in what has been a steady, if small, stream of such prosecutions across the country since the late 1980s. They represent the extreme end of a once-derided perspective that is gaining considerable currency in the world of HIV prevention. With the U.S. epidemic larger -and blacker -than it's ever been, the growing consensus among health officials and community activists alike is that the only way to stop the virus' spread is to control the behavior of those who already have it. An increasingly popular quip bouncing around the halls of AIDS conferences sums up the new zeitgeist. Every instance of HIV transmission, one knowingly remarks, involves someone who's HIV positive. This truism ignores its corollary: There's always a negative person in the mix, too. From tuberculosis to syphilis, Western public health has long employed a straightforward and largely successful formula to controlling communicable diseases: find the carriers, treat them, determine who they may have already infected and repeat. Confine those who can't or won't cooperate. Why not adopt this "screen and treat" approach to HIV? Science can't expunge the virus from folks' bodies, but it can suppress it to low enough levels that it's harder to transmit. And there's at least some research that shows people who are engaged in treatment are less likely to do things to risk exposing others to the virus. But HIV has never been just another communicable disease; it's passed on by used needles and sex, often of the taboo sort, be it between men or just outside of marital monogamy. So for years, HIV prevention considered the complicated emotions that drive sexual behavior, from the quest for intimacy to the urge for adventure, to be far too layered for single-bullet solutions. Health educators held transmission's duality as their guiding principle-it takes two to do the AIDS tango-and crafted campaigns that urged every individual to take personal responsibility for his or her own health. But after 25 years of this approach, the epidemic is still raging out of control. In June, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that more people are now living with HIV than ever before-over a million, with an estimated 40,000 new infections a year. African Americans account for just under half of those already infected and over half of new infections each year. In a shocking CDC study also released in June, researchers found 46 percent of the black homosexual and bisexual men they tested in five major cities were infected. Indeed, no matter how you chop up the numbers-by gender, sexuality, geography-African Americans in particular and Latinos to a lesser extent are now the predominant face of HIV. So as the epidemic grows more entwined with the fabric of our lives, those who have been tasked with stopping it have grown terribly frustrated. At a packed public forum in New York City this March, convened in response to local health officials' announcement of a potential new and virulent strain of HIV (which has since proven nonexistent), the anger in the voices of AIDS veterans was palpable. Tokes Osubu, executive director of the New York-based group Gay Men of African Descent, articulated why. "My anger stems from seeing that someone in his mid-40s, who had seen the devastation of the 80s and 90s, [became HIV positive] in 2004. That made me extremely angry," Osubu somberly admitted, "and angry because I thought that as a provider [of AIDS services] I had failed." Those sort of haunting doubts have driven HIV prevention veterans to reconsider the traditional public health tools they once shunned. Policing and Prevention Western efforts at disease control have been firmly rooted in paternalism and policing from their inception. The German doctor Johann Peter Frank first spelled out the state's responsibility-and authority-for maintaining a healthy citizenry in a series of groundbreaking, turn-of-the-19th century volumes, aptly titled A System of Complete Medical Police. It was a soup-to-nuts guide on what people needed to do to stay healthy, and how the state should encourage that behavior. Predictably, moralism was a recurring theme-one infamous section urged local officials to place time limits on dances that seemed too erotic, like the waltz. That top-down perspective on prevention has persisted, and it informed government's initial response to HIV. Washington had just begun noticing AIDS' decade-old carnage when, in 1990, Congress passed the Ryan White CARE Act, which is now the federal government's primary vehicle for funding AIDS services. Lawmakers included a provision demanding that every state have a criminal code that allows it to prosecute a person's failure to disclose an HIV diagnosis to someone who may be put at risk by it. The resulting state laws vary greatly in both form and severity, but they fall roughly into three categories: those that specifically criminalize the failure to disclose an HIV infection; those that enhance penalties to existing crimes-prostitution, rape, assault-when the person charged is positive; and those that simply use general laws like assault to prosecute "intentional" attempts to infect someone with HIV. According to the HIV Criminal Law & Policy Project, as of 2000, 24 states had laws that directly address situations like Carriker's, in which a person fails to disclose his or her status before sex. Sentence enhancements are on the books in 15 states, most of which also have specific disclosure laws. The laws, according to a review done by scholars at the Center for AIDS Prevention Studies at University of California San Francisco, largely require simply that the positive partner in a sex act was aware of his or her status and didn't reveal it. Transmission is not required by any state, and using a condom gets you off the hook in only two. The penalties get as high as a life sentence, such as in Washington State, but are typically in the range of 7-15 years per count, such as the Georgia law Carriker faces. A handful of states raise the prosecutorial bar, adding that the person must have had harmful intent to be guilty of a crime. Because the cases are difficult to win-you must prove something did not happen, and usually do it without witnesses-actual prosecutions are rare and seem to come in only slam-dunks. The HIV Criminal Law & Policy Project reviewed legal and media databases from 1986 to 2001 and found evidence of just 316 prosecutions-in 80 percent of which the defendants were convicted. But prosecution isn't really the point. Supportive lawmakers believe they don't need to lock up every potential offender, just send a scary enough message to make them think twice about having sex without disclosing. Problem is, no research whatsoever exists to show these laws and their messages actually aid prevention. To the contrary, there's plenty reason to believe they hurt it. Does Targeting Positive Folks Work? Many people would agree that someone who knowingly sets out to infect others with a communicable disease needs to be confined from society. But HIV's epidemiology suggests the primary reason people who are positive have unprotected sex or share needles with others is that they don't know they're positive. CDC estimates a quarter of those living with HIV don't know it. African Americans particularly are operating blind: In the June study on black gay men, two-thirds of those who tested positive were unaware of their infection at the study's outset. There are myriad reasons for black folks' reluctance to get tested-we don't think we're at risk, don't trust healthcare providers, don't even have healthcare providers. But many people working in black and Latino communities say the real problem is one that targeting positive folks worsens. "The answer, at least partially, is stigma," Latino Commission on AIDS Executive Director Dennis DeLeon told the March New York City forum. "Stigma associated with even taking an AIDS test. The stigma associated with going to medical care once you learn about your HIV status. These stigmas are very heightened in people of color communities," DeLeon warned, adding, "I have not seen enough" work on that fact. Keith Folger, director of programs for the National Association of People With AIDS (NAPWA), adds that the focus on forced disclosure also does little to address the epidemic's driving forces. "Just because I tell you I'm positive, that doesn't mean that we're going to behave differently" when having sex, he notes. NAPWA has long advocated for prevention efforts targeting people who are positive, but only as part of a larger suite of work and combined with efforts to reduce the stigma that drives many into the HIV closet. "There are so many reasons not to disclose, it just can't be the only answer," Folger argues. "What if negative people said, 'I just refuse to be the receptive partner in sex without a condom?' We say it's a shared responsibility." Ultimately, for all the talk about sending messages to people who are positive, the real message of criminalization laws may be to everyone else: this troubling and complicated epidemic isn't your problem, it's that of monstrous outsiders who we can simply wall off from regular folks' lives. It is perhaps telling that the highest-profile and most aggressively pursued prosecutions have featured America's most recurring monster fantasy-young black men from urban areas who were having sex with young white women in rural areas. In 2004, a black man named Anthony Whitfield in Washington State faced 137 years in prison for, as his public defender put it to the Seattle Weekly, "spreading AIDS to a bunch of white women." Seventeen women accused Whitfield of having sex with them without disclosing. In 2002, prosecutors in Huron, South Dakota locked up black college freshman Nikko Briteramos, a Chicagoan who had just come to the small, largely white town on a basketball scholarship, for having sex with his white girlfriend without disclosing. He'd tested positive just a few weeks before the sex act. But Nushawn Williams remains the unlucky poster child of the HIV criminalization movement. Williams was a 20-year-old, black Brooklynite who had relocated to a small, economically-depressed and largely white town in upstate New York to exploit its wide-open crack market. Williams commuted back and forth to New York City, and once, while in jail there on an auto theft charge, he tested HIV positive. He received no counseling or support in learning how to live with his infection. Nevertheless, he readily gave health workers the names of the 20 or so women around the state with whom he'd recently had sex. As is routine, caseworkers tracked the women down over the course of a year, and four tested positive. Meanwhile, six women whom he hadn't named tested positive when they went for exams without having been summoned. County health officials noticed that these women included Williams in their own partner-notification lists. So they declared an emergency, had confidentiality laws waived and put up posters that both identified Williams and encouraged anyone who had had sex with him, or even had had sex with someone who had sex with him, to come in for a test. In the ensuing national media spectacle Williams was called everything from the "devil" to "boogeyman incarnate" to "super infector"-a riff on the then-popular "super predator" caricature for young, urban black men. This August, news reports from tiny Milford, Iowa, suggested it may host the next installment in this series. Police there had just locked up Dewayne Boyd, a black man in the largely white town, charging Boyd with having had sex with four women-including his wife-without disclosing his HIV infection. As one resident told the Des Moines Register, "What bothers me is that people are saying, 'It's that black guy.'" A Slippery Slope The CDC has plunged into this volatile atmosphere with an aggressive new initiative it is calling "Advancing HIV Prevention." In 2003, the government announced that their prevention money would now be focused on campaigns that seek to first identify and then alter the behavior of positive people. That means more testing campaigns, but it also means emboldened partner notification programs-in which people who test positive are pushed to reveal their sex partners and aid the health department in tracking them down. Very few of those in the mainstream AIDS community who support this invigorated focus on the behavior of positive people also stand behind HIV criminalization laws. But critics of the new CDC initiative warn that, when handled poorly, it's a slippery slope from "targeted prevention" to the sort of plain scapegoating those laws represent. NAPWA's Folger worries that, while the CDC's emphasis on testing is important, the agency's push to make it "routine" -- or, just part of any hospital or doctor's office visit -- is ill-advised as long as the strong stigma associated with the virus remains. Just learning your HIV status, he notes, appears to change behavior in the long term, but in the short term it can be catastrophic if the person isn't prepared for that knowledge. A not untypical reaction is that of Williams and Briteramos: to simply choose denial, ignore the diagnosis and go on with life as usual, thereby becoming a criminal. Folger also questions the genuineness of Washington's commitment, given that Congress is now considering a funding cut for prevention and continues to undermine proven methods for stopping the virus' spread. "One of the most effective forms of prevention for positives, our federal government refuses to fund," he scoffs, "and that is needle exchange." A longstanding law forbids any federal money to be used for such programs. To Folger, any real effort to encourage safety among positive folks needs to come from the bottom up and focus on helping rather than policing them. "You ask those of us living with HIV, 'What messages work?' Is it a women's group that teaches women to use female condoms, so that their partners don't even know that they're having safe sex?" he posits. "You start with the infected population and say, 'What do you think it is that will work for you?'"

Hundreds of AIDS activists from around the country converged on Washington, D.C., this weekend to demand policymakers invest resources in stopping the virus’ spread and treating those who are already positive. The march coincides with what is shaping up to be a crucial week on Capitol Hill, in which lawmakers will decide whether to embrace deep budget cuts to several safety net programs crucial to poor people living with HIV/AIDS. Republican leaders in the House of Representatives are pushing an omnibus spending bill that would cut $50 billion from the federal budget for social service programs over the next five years. The vote comes as representatives also prepare to vote on the fifth tax cut in five years, totaling $70 billion. Medicaid would bear a large chunk of the proposed cuts to service programs. The House bill trims the program by $12 billion over five years and $48 billion over the next ten years. The bill achieves these savings in large part by opening the program to copays and premiums for the first time, charging patients from $3 to $5 per doctors’ visit or prescription. A Congressional Budget Office analysis predicted those steps would achieve the desired savings not by bringing in actual revenue but by acting as a disincentive for poor people to actually use the program. Medicaid is the largest payer for AIDS treatment in the nation, with almost half of those receiving care doing so through the program. Sixty-four percent of HIV-positive African Americans getting treatment pay for it with public health insurance. The House bill would also cut $844 million out of the food stamps program over the next five years, largely by changing the rules to disqualify tens of thousands of legal immigrants from the program. New rules would require immigrants live in the United States for seven years before becoming eligible for food aid; currently they must reside in the U.S. for five years. AIDS service providers often complain that clients are unable to take the steps needed to both stay healthy with HIV and to prevent its further spread because they are overwhelmed by basic daily needs, in particular the costs of food and transportation to and from jobs or clinics. The House bill would further cut nearly $400 million from the foster care program by denying foster care payments to relatives who take in children who have been removed from their parents’ homes by court-order. These and other provisions in the House bill up for consideration this week are far more drastic than those passed by the Senate last week. The Senate’s budget-cutting measure stripped $35 billion from federal expenses over the next five years. The Senate bill passed Thursday night, Nov. 3, largely along party lines, with only two Democrats voting for it and five Republicans against it. But even the bill’s critics have noted that the senators found relatively painless ways to slash spending in social services. It would save $36 billion over the next decade by getting rid of a piece of the new Medicare drug-benefit program that would give managed care companies financial incentives to participate in the now partially privatized program. And it focuses much of its Medicaid and Medicare cost-cutting energy on reducing fraud by hospitals and nursing homes. The Senate bill also included a provision that would set aside $450 million to aid states that try opening Medicaid to people who have tested HIV positive but are not yet diagnosed with AIDS. Currently, Medicaid eligibility is limited to those with an AIDS diagnosis, because only people with full-blown AIDS are considered disabled. For years, AIDS advocates have urged a widening of the program, noting that early access to treatment is often what separates those who live with and die from HIV. Once the House votes on its budget bill, the two versions must be reconciled before being sent to President Bush. But the White House has threatened to veto the final budget bill if it includes the Senate’s plan for reducing Medicare costs. Meanwhile, 10 caravans from 100 cities across the country arrived in D.C. on Saturday, part of a year-long initiative to re-energize AIDS activism and demand action from national and local policymakers. Dubbed the Campaign to End AIDS, the participants were scheduled to march on the White House on Monday, Nov. 7, and assemble a mock cemetery to symbolize those who have died from AIDS. The following day, activists will hold a press conference with the Congressional Black Caucus and visit each congressional office to discuss federal AIDS policies.

One in four people receiving care in the U.S. for an HIV infection report experiencing discrimination from a health care provider, according to a new study. And more than half of them cite their physicians as the individual who discriminated against them. The study, published in the current issue of the Journal of General Internal Medicine, also noted a strong association between reported discrimination and indicators of poor quality care. The study’s authors, led by University of California, Los Angeles professor and RAND Corp. researcher Dr. Mark Schuster, reviewed data from a 1996-1997 survey of 2,466 adults infected with HIV, which was part of a massive healthcare study known as the HIV Cost and Utilization Study. A third of the survey participants were Black and 15% were Latino. The respondents were overwhelmingly male, at 77%. The survey asked participants if they had experienced any one of four types of discrimination while getting care: if a provider had been “uncomfortable with you,” “treated you as inferior,” “preferred to avoid you,” or refused service. Twenty-six percent of those interviewed answered yes to at least one of these questions, with the highest number, 20%, saying their healthcare provider had been uncomfortable with them. Eight percent said they had been refused service. African Americans were the least likely group to report discrimination. While 32% of whites and 21% of Latinos said they had been treated differently because of their HIV status, only 17% of Blacks said the same. Schuster’s team, however, suggested the racial differences may say more about expectations than actual treatment. “African-Americans and Latinos may typically experience worse care and thus be unaware that better care exists,” the researchers wrote. Meanwhile, they posited, white male HIV patients may be experiencing the “black sheep” effect, where “clinicians might feel more hostility to people who are generally similar to themselves except for characteristics that they view negatively, such as being gay or having HIV.” But Schuster’s team also stressed that the findings are narrow: They show only that lots of people getting care for HIV feel like they are being treated differently. The study did not measure actual behavior of providers. The researchers urged clinicians to be mindful of conditions that may foster the perceived discrimination, “whether real or misunderstood.”

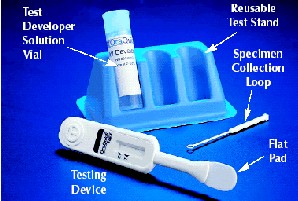

A do-it-yourself HIV test that provides results in as few as 20 minutes will face review from a key advisory panel of the Food and Drug Administration this week, which will decide whether to recommend the test for over-the-counter sales. On Thursday, Nov. 3, the FDA’s Blood Products Advisory Committee will consider whether the OraQuick Advance test should be available in drug stores. The panel’s decision will serve only as a recommendation, but the FDA usually follows the advice of its advisory boards. If ultimately given the go ahead by the FDA, the OraQuick test will be the first HIV test the FDA has approved to be administered without a healthcare provider on hand, moving the process of learning about an HIV infection from the controlled if cumbersome environs of clinics and doctors’ offices to unmonitored but far more accessible settings. OraQuick is already widely used in clinics and doctors’ offices. The OraQuick test, manufactured by OraSure Technology in Bethlehem, Pa., is done by taking a swab of fluid from inside of the mouth and then testing it for the presence of HIV antibodies. It has proven accurate 99 percent of the time – on par with the traditional blood tests – though must be confirmed with a follow up blood test. OraSure told the Associated Press that it has not yet decided how much it would charge for the over-the-counter version of the test, but it now sells the kits to healthcare providers for $12 to $17. The FDA first approved what is known in HIV parlance as “rapid testing” in 2003. OraQuick is one of four rapid tests that have won the agency's stamp of approval for use in healthcare settings. Since its debut, both public health officials and AIDS activists have praised the technology for helping to get more people tested. Typically, an HIV test requires a two-step, multi-week process. Individuals must first come and get blood drawn, then wait while that blood is sent to a lab and tested. They are usually asked to return in person to receive the results. Public health officials complain that far too many people never make it to the end of that process. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about a third of those who get tested each year disappear before learning the outcome, leaving a quarter of all test results undelivered. The CDC also estimates more than a quarter of the one million Americans living with HIV do not know they are infected, and thus are less likely to take steps to prevent passing the virus on to others. The problem appears to be a particularly acute one for African Americans, who account for just under half of all people living with HIV in the U.S. In June, the CDC released the first in a series of behavioral studies that it is using to draw a more detailed portrait of the epidemic and its driving forces. In that study, which focused on homosexually and bisexually active men, 67 percent of positive Blacks were undiagnosed. As a result, many of those working to stop HIV’s spread welcome new technology that makes HIV testing more accessible, and see OraQuick’s potential move from the staid confines of a clinic to the easy-access shelves of drug stores as a leap forward. “Overall, I would say they are a step forward,” said departing National Association of People With AIDS Executive Director Terje Anderson, talking to the Associated Press. “Anything that helps more people learn their status is a good thing.” But rapid testing, even in a doctors’ office, is not without its critics. Some argue that the wait time between getting tested and learning the results can be useful, and that those who fail to return aren’t ready to deal with the answer the may get. While studies show that, in the long term, learning about an HIV infection reduces the likelihood that a person will engage in behavior that may spread it, there are no guarantees of a benefit in the short term. Some people simply go into denial; others react by actually increasing their risky behavior. The emotional and social minefields that surround HIV testing have for years led the CDC and others to insist that tests be accompanied by counseling and the presence of healthcare workers who can help guide someone who has just learned about an infection to resources for help dealing with it. But in recent years the CDC has pushed to expand HIV testing, making it a far more “routine” part of doctors’ visits and other healthcare encounters. Critics say the agency risks going too far, stripping the process of crucial supports.

Positive Poetry

A Newark, N.J.-native, 26-year-old baron. is a rising poetic talent. His debut album, Troubled Man, blends hip hop and spoken word in pieces that tell the story of a young, Black and unapologetically gay life. In a year in which public health watchers have groped for answers about why HIV infection rates are climbing among young gay men, baron.'s art -- while not dealing directly with the epidemic -- offers insight into the challenges young Black same-gender-loving men face in their love and sex lives. In one track on Troubled Man, "cuz yur beautiful," baron. declares, "Brothers I love you, openly/Because that's the only way I know how." Here, baron. offers a poem on "the blacks, the gays" for BlackAIDS.org. Birds Fly High early morn, I slept unsure of never was if it wasn’t for the hawk’s eye it’s been too easy calling on the gays not a wave goes by, I don’t inhale freedom is mine, I know how I feel To see more of baron's work and hear selections from his album, visit his website.

kind of lightly touched indecency

and I really wasn’t all right

big blue whales swimming awry

my sake will still consider falling

and for this alone, I write to music

even easier on us to let it stain

a long walk from social circles

can return us back to the sun

where many a stories shared by one

what most have discovered later

decimation comes in partial pictures

can the blacks ever leave a scar

to their young with wanted savor

but if us aloud was stretched

across of many hues open wide

for nothing else, I would rest a lie