How Obamacare Went South In Mississippi, Part 6: Patchwork Solutions

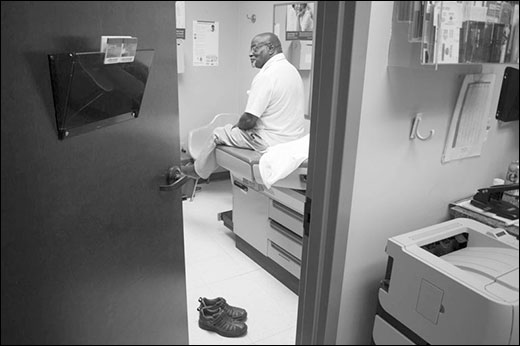

Robert Martin, 73, waits to see Dr. Tim Alford at the family practice clinic across from Montfort Jones Memorial Hospital.

In the country's unhealthiest state, the failure of Obamacare is a group effort. Go here to read Part 5.

The white sand and salty air of the Mississippi Gulf Coast are far removed from the kudzu draped trees surrounding Oak Hill Baptist Church hundreds of miles away near the Tennessee border. Yet, a few months into open enrollment, necessity forced the ground to close.

Gulf Coast community advocates were feeling overlooked and complained that there were no permanent navigators in two of the state's largest cities—Biloxi and Gulfport. Rev. Alice Graham, executive director of Gulfport-based Interfaith Partnerships, a religious group eager to aid the uninsured, told me the university hospital UMMC, in particular, had rebuffed her efforts at local partnerships and seemed not to understand the Coast's diverse population and need for translated materials. With its Latino service workers and Vietnamese shrimpers (men fishing; women peeling), the Gulf Coast is Mississippi's most heterogeneous region.

Although Roy Mitchell's outfit in Jackson, Mississippi Health Advocacy Program, had been passed over by federal grant makers, his team and Oak Hill came up with a patchwork solution: Minor would let community organizers across the state, including Graham, use his federal grant authority to become certified navigators. As a result, the number of counselors working under the auspices of tiny Oak Hill jumped to 60 by November, including a handful along the Gulf Coast. The workaround gave Graham boots on the ground. Mitchell's group scrounged up $15,000 to help her pay Hispanic and Vietnamese navigators a small stipend, and her team of six set about their work in Gulfport.

Meanwhile, in nearby Biloxi, community health centers, which offered basic medical care to the uninsured, were seeking out patients who could qualify for Obamacare plans. The Coastal Family Health Center, a modern and spacious low-cost clinic, sits along a desolate patch of Main Street where a sign at Nance Temple Church of God in Christ preaches: "Think it's hot now. Don't miss heaven and go to hell!"

Because clinics like Coastal Family Health Center were trusted faces in low-income communities, federal administrators saw them as vital partners in the enrollment campaign. A quirk in the health law had severely limited funds for official navigator grants in states that relied on healthcare.gov, like Mississippi, but federal agencies were free to direct $150 million to the nation's 1,100 community health centers. Mississippi's clinics received $2.5 million—twice that awarded to UMMC and Oak Hill.

Danielle Davis-Polk, who led Coastal's signup campaign, and her five-person team staged healthy cooking events and streetside fairs to drum up insurance shoppers. But their efforts along the shoreline ran into familiar troubles: Local employers didn't want anything to do with Obamacare.

"They don't want to talk to us," Davis-Polk told me in her office in Biloxi as apocalyptic-looking storm clouds gathered outside her window. Employees would "sometimes say, 'Well, can you come back and talk to us when the owners are not here?''' A hospital housekeeping service refused to talk to her staff, Davis-Polk said, as did the Beau Rivage casino, which had recently reduced some workers' hours to part-time and dropped those workers' health coverage. Davis-Polk chose not to attribute the pushback to politics, and instead hoped it was simply a matter of educating people about the health law. Still, she struggles to understand how to reach resistant employers. "What that conversation sounds like to even get them to listen, I don't know," she said. "We've had people tell us, 'No, don't leave flyers. We're not interested.' And I just don't understand that." It was not lost on her that those uninsured employees occasionally ended up at the emergency room or Coastal's clinics.

Black pastors proved more receptive to both Davis-Polk's and Rev. Graham's overtures, but converting the pulpit's enthusiasm into actual customers was difficult. (White-dominated Southern Baptist churches generally oppose the ACA.) The black churches were supposed to deliver Obamacare customers in droves, but the state's dismal signups suggested otherwise. At Graham's own United Methodist church, parishioners would promise to attend a signup event. "'Oh yeah, Dr. Graham! We're gonna come!'" she recalled them telling her. "And then they don't come." The same happened when she handed out fliers and staged events at neighboring African-American churches. "You have to be willing to be disappointed and still go back and still do the work," says Graham.

Graham attributed black residents' reluctance to a wariness of government interest in their plight. At 68, she had lived through painful years prior to, and after, the civil rights movement, and the president's own black heritage didn't mollify the distrust. "African Americans in this area have had so many experiences where the government has let them down. To say the government is going to do something? Is going to protect them?" Graham's voiced slipped into an exaggerated dialect. "Really? We been black a l-o-n-g time."

Just as devastating floods and hurricanes had shaped Mississippi's terrain, generations of living at the bottom of the heap begot apathy and resignation in Mississippi's poor—black and white. To hell with committees and outreach strategy; when it comes right down to it, Graham says, the predominant view among the poor is: "Mississippi dun't care about its poor people." She was wary of wading into politics—she runs a non-partisan group that relies primarily on private dollars—but the message trumpeted by the state's white Republican politicians was clear to her. "If you're poor, you deserve to be 'cause if God really loved you, you'd have money, you'd have access, you'd have resources," Graham told me. "That's Mississippi values."

The poor had come to believe it themselves. "That's just the way it is. You got to go to a hospital? You go, and you sit and wait in the emergency room. That's what poor people do."

By Sarah Varney

Jeffrey Hess of Mississippi Public Broadcasting contributed to this story.

This article was reprinted from Kaiser Health News with permission from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent news service, is a program of the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonpartisan health care policy research organization unaffiliated with Kaiser Permanente.