In This Issue

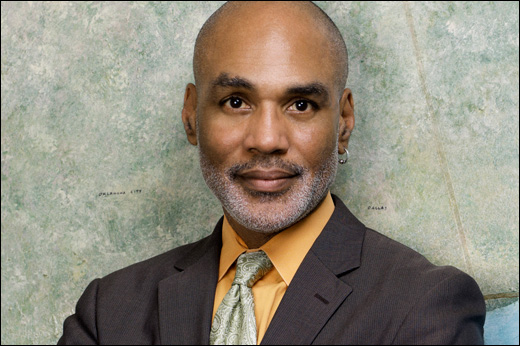

We lost a giant this past weekend with the passing of veteran journalist, George Curry, from a heart attack. George was a hero, a mentor, a father figure, a friend to so many people, including me and maybe even especially me.

I'll never forget the first time I met George 13 years ago. He was an old-school journalist straight out of central casting. At the time he was the editor-in-chief of the National Newspaper Publisher's Association (NNPA) news wire, Black Press USA. Marriage equality was relatively new in the media at the time. George wrote a piece where he said that he was ambivalent about gay marriage and laid out arguments in favor of and opposed to it, in an effort to show the conflict about the topic that was going on within Black communities and among Black leaders.

As one might imagine, the LGBT community took great offense at the column. Many people in the community began to attack George. Eventually I began to receive telephone calls about this "homophobe" at the NNPA. I asked if anyone had called George; had anyone bothered to talk to him? And as far as I could tell, no one had. So I called him up. I said, "My name is Phill Wilson and I'm President and CEO of the Black AIDS Institute, and I want to come and meet you." He said, "Sure, when do you want to come?" We set an appointment, I bought a ticket and flew to Washington, D.C., to meet with him at his office on Howard's campus. We had a great conversation. To my surprise George was not homophobic, he was simply trying to figure it out.

To my greater surprise, though, he was not sufficiently informed about the latest information on HIVAIDS and Black communities. At the end of the meeting, George shared with me that even though he had gotten lots of negative mail — primarily from the LGBT community—that mail had been dwarfed by the positive mail he had gotten from the Black community. Even so, George promised to do two things: 1) he would run the pro-gay-marriage comments he had received; 2) he invited me to write a counterpoint column that he would also run. I suggested that he invite Kai Wright, whom he knew, to write the counterpoint, and he did.

After I left George, I didn't understand it, but I felt like something had changed—and, boy, was that an understatement! George became my biggest advocate, cheerleader, coach, mentor, big brother. We traveled around the world attending International AIDS meetings for the next 17 years and he transformed the coverage of HIV/AIDS and LGBT issues in the Black media. There was not a single time during the course of our friendship when I called George to ask for help that he didn't immediately do whatever he could. As I have come to meet other people who knew and worked with him, I've learned that my experience was not unique. If he believed in you or believed in an issue, he was all in. That first meeting reinforced an important lesson that has guided my work as an AIDS activist: to meet people where they are and to see people in ways that are different and broader than your preconceived biases.

I don't know how long it will take us to process the magnitude of this loss, let alone to fill the hole left by the passing of our great friend. I know that I'm not yet ready to say goodbye. Maybe the best that I can do is to make sure that my actions and words are worthy of George's friendship and support. The last conversation I had with George consisted of him pushing me, as he always did, to write my autobiography. His voice is still in my ear: "You have to do this, Phill—we need a deadline. You owe it to yourself and you owe it to the world." My heart and prayers go out to his longtime companion Ann Ragland, and his family.

As a tribute to George, in this issue we're running several of his pieces—the final three stories he wrote in July as a member of the Black AIDS Delegation to the International AIDS Conference in Durban. We are also running the bio from his Heroes in the Struggle award, and the piece he wrote in 2003 that brought George and me together.

Yours in the struggle,

Phill