How Obamacare Went South In Mississippi

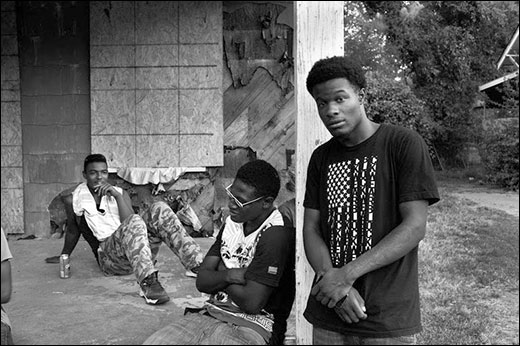

Young people in Mississippi are dealt a tougher hand than those in most other states. The state ranks last in life expectancy, per capita income, and children's literacy. Here, three young men hang out on Winter Street in Jackson, the state capital.

In the country's unhealthiest state, the failure of Obamacare is a group effort. The first in a series from our friends at Kaiser Health News. The lunch rush at Tom's on Main in Yazoo City, Mississippi, had come to a close, and the waitresses, having cleared away plates of shrimp and cheese grits, seasoned turnip greens and pitchers of sweet tea, were retreating to the counter to cash out and count their tips.

It didn't take long: The $6.95 lunchtime specials didn't land them much, and the job certainly didn't come with benefits like health insurance. For waitress Wylene Gary, 54, being uninsured was unnerving, but she didn't try to buy coverage on her own until the Affordable Care Act forced her to. She didn't want to be a lawbreaker. Months earlier, she had gone online to the federal government's new website, signed up and paid her first monthly premium of $129. But when her new insurance card arrived in the mail, she was flabbergasted.

"It said, $6,000 deductible and 40 percent co-pay," Gary told me at the check-out counter, her timid drawl giving way to strident dismay. Confused, she called to speak to a representative for the insurer Magnolia Health. "'You tellin' me if I get a hospital bill for $100,000, I gotta pay $40,000?' And she said, 'Yes, ma'am.'"

Never mind that the Magnolia worker was wrong — her out-of-pocket costs were legally capped at $6,350. Gary figured with a hospital bill that high, she would have to file for bankruptcy anyway. So really, she thought, what was the point?

"This ain't worth a tooth," she said.

She canceled her coverage.

The first year of the Affordable Care Act in Mississippi was, by almost every measure, an unmitigated disaster. In a state stricken by diabetes, heart disease, obesity and the highest infant mortality rate in the nation, President Barack Obama's landmark health care law has barely registered, leaving the country's poorest and perhaps most segregated state trapped in a severe and intractable health care crisis.

"There are wide swaths of Mississippi where the Affordable Care Act is not a reality," Conner Reeves, who led Obamacare enrollment for the University of Mississippi Medical Center, told me when we met in the state capital of Jackson. Of the nearly 300,000 people who could have bought coverage, just 61,494—some 20 percent—did so. When all was said and done, Mississippi would be the only state in the union where the percentage of uninsured residents has gone up, not down, according to one analysis.

To piece together what had happened in Mississippi, I traveled there this summer. For six days, I went from Delta towns to the Tennessee border to the Piney Woods to the Gulf Coast, and what I found was a series of cascading problems: bumbling errors and misinformation ginned up by the law's tea party opponents; ignorance and disorganization; a haunting racial divide; and, above all, the unyielding ideological imperative of conservative politics. This, I found, was a story about the tea party and its influence over a state Republican Party in transition, where a public feud between Gov. Phil Bryant and the elected insurance commissioner, both Republicans who oppose Obamacare, forced the state to shut down its own insurance marketplace, even as the Obama administration in Washington refused to step into the fray. By the time the federal government offered the required coverage on its balky healthcare.gov website, 70 percent of Mississippians confessed they knew almost nothing about it. "We would talk to people who say, 'I don't want anything about Obamacare. I want the Affordable Care Act,'" remembered Tineciaa Harris, one of the so-called navigators trained to help Mississippians sign up for health insurance. "And we'd have to explain to them that it's the same thing."

Even the law's vaunted Medicaid expansion, meant to assist those too poor to qualify for subsidized private insurance, was no help after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states could opt out. Gov. Bryant made it clear Mississippi would not participate, leaving 138,000 residents, the majority of whom are black, with no insurance options at all. And while the politics of Obamacare became increasingly toxic, the state's already financially strapped rural hospitals confronted a new crisis from the law's failure to take hold: Facing massive losses in federal subsidies imposed by the law and seeing no rise in new Medicaid patients, hospitals laid off staff and shuttered entire departments.

"We work hard at being last," snarked Roy Mitchell, the beleaguered executive director of the Mississippi Health Advocacy Program, about the state's many missteps.

With the first year of open enrollment behind them, Mississippi's small cadre of health advocates were feeling beaten down and betrayed by the Obama administration and its allies who, they suspect, viewed Mississippi as a lost cause and had directed their efforts elsewhere.

"Even a dog knows the difference between being tripped over and being kicked," Mitchell added.

A RURAL GHETTO

It is hard to find a list where Mississippi doesn't rank last: Life expectancy. Per capita income. Children's literacy. "Mississippi's people do not fare well," wrote Willie Morris, a seventh-generation, native son who grew up in Yazoo City, once a bustling trading center perched on the southern edge of the cotton-rich Delta. Today, nearly half of Yazoo City's residents live in poverty; its people, like the Delta's vast swamps, have been drained away.

While neighboring Southern states ushered their agricultural economies into the modern world — building vibrant, commercial engines like Birmingham, Atlanta and Charlotte with opportunities for blacks to move into the middle-class — Mississippi remains a rural landscape. Signs of the impoverished post-Civil War South are everywhere: irrepressible kudzu vines pressing into the glass door of an abandoned building; tipsy wooden shacks that look at first glance neglected and forlorn are instead occupied with life. "The Depression, in fact, was not a noticeable phenomenon in the poorest state in the Union," wrote Eudora Welty, when she photographed Mississippi in the 1930s. It remains the poorest state today: 22 percent live in poverty.

None of which bodes well for the health coverage of the state's 3 million people. Small businesses that dominate the economy typically don't offer health insurance, and despite its residents being down-at-the-heels, Mississippi's public health program for the poor is one of the most restrictive in the nation. Able-bodied adults without dependent children can't sign up for Medicaid no matter how little they earn, and only parents who earn less than 22 percent of the federal poverty level — about $384 a month for a family of three — can enroll. As a result, one in four adult Mississippians — cashiers, cooks, housekeepers, truck drivers — goes without coverage. And African-Americans carry much of that burden: one in three adults is uninsured, compared to one in five whites.

It is difficult to untangle the state's dismal health — rampant obesity, diabetes, heart disease —from its antebellum past. Generational upward mobility happened elsewhere; here, families have remained poor and undereducated, holding out against change wrought by the New South. The practice of going to a doctor for preventive care continues to lag in Mississippi for practical reasons, including no insurance and little money, but also for cultural ones. For blacks, there remain deep wells of distrust dating back to Jim Crow laws that barred them from the front doors of doctors' offices, and to when black women were routinely sterilized in what became known as "Mississippi appendectomies." As a result, Mississippians are less likely than the rest of the country to seek primary care for chronic conditions and more likely to turn to hospitals when those ailments become more serious and expensive.

Gruesome ends await.

Mississippi has the highest rate of leg amputations in America and the lowest rate of Hemoglobin H1c testing, used to monitor and prevent diabetes complications. The amputation rate for African-Americans is startling: 4.41 per 1,000 Medicare enrollees versus 0.92 for non-blacks. The state also has high breast cancer death rates, even though it has a low breast cancer incidence rates. The cancer often isn't found until it's too late.

Next week, how the Tea Party undermined Mississippi Republican's plans to implement an online health insurance marketplace.

By Sarah Varney

Jeffrey Hess of Mississippi Public Broadcasting contributed to this story.

This article was reprinted from Kaiser Health News with permission from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent news service, is a program of the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonpartisan health care policy research organization unaffiliated with Kaiser Permanente.