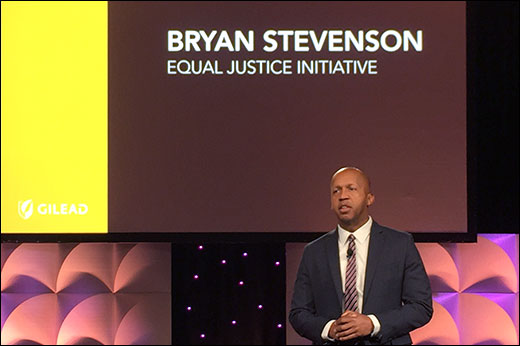

Bryan Stevenson Urges USCA Audience to "Get Proximate"

Bryan A. Stevenson, founder and Executive Director, Equal Justice Initiative, a private, non-profit organization headquartered in Montgomery, Alabama. Stevenson is also a professor at New York University School of Law

At Friday's plenary luncheon, Bryan Stevenson, executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), spoke to conference attendees about the connections between the AIDS movement, the movement to end mass incarceration, and other social justice work.

"We have to do something to push against forces that created mass incarceration and excessive punishment," said Stevenson, a public-interest lawyer who successfully argued a recent Supreme Court case that ended mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles 17 years-old or under. EJI provides legal representation to indigent defendants and others who have been denied fair and equal treatment in the justice system.

Stevenson offered the audience four pieces of advice.

First, he said, it is important that people in the AIDS movement get close to the problems and the people who are experiencing them.

"We cannot make good decisions from a distance," said the author of the New York Times bestseller, A Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, his memoir. "If you are not proximate, you cannot change the world."

Proximity empowers and changes you, said Stevenson, who shared the story of his first work-related visit to a man confined to death row as a law-school student who felt ill-equipped for the task. However, during that visit he learned that he had something to offer. "You're the first person I've talked to who was not a death row prisoner or a death row guard," said the man, who, with a death sentence hanging over his head, had found it too difficult to see his wife and family.

"I couldn't have guessed that, even in my ignorance, being proximate could have an impact on someone's life," Stevenson said, as he urged audience members not to run from low-income or other suffering people.

"There is something for you there," he added. "If you get proximate, you will find the answer to HIV infection. You will find it in the communities where people are suffering and struggling."

Next, Stevenson emphasized the importance of changing the narrative around.

"The problems we are dealing with are not just defined by a virus; a narrative sustains these problems," he said. "The narrative is the politics of fear and anger." He and his staff have won reversals, relief or release for more than 115 wrongly condemned death-row inmates. He observed that politicians fall over each other to be seen as tough on crime, but that nobody wants to talk about rehabilitation, compassion, redemption or mercy, including for children.

Stevenson identified this narrative as part of the legacy of slavery.

"We created this great evil," he said, but when we discuss it today, "We talk about involuntary servitude or forced labor, but we don't talk about White supremacy." The nation also overlooks the Southern legacy of lynching, he said, referring to EJI's investigation, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror. "The demographic geography of HIV was shaped by this era of racial terror," Stevenson added, noting that the Great Migration of Blacks from the rural South was driven by their desire to escape terrorism. Today, both areas have high HIV rates.

Stevenson also told audience members to protect their hopefulness.

"Hope will get you to stand up when other people are telling you to sit down and to speak when other people will tell you to be quiet," he said.

Finally, Stevenson urged the audience to step outside of their comfort zone.

"We're programed to do what's comfortable," he said. "If we want to end the HIV epidemic, or change the world or create more justice, we sometimes have to do uncomfortable things. Sometimes choose to do an uncomfortable thing because it's the necessary thing."

Hilary Beard is the editor-in-chief of the Black AIDS Weekly and is a freelance health writer living in Philadelphia.